How this turf education program is helping solve one of golf’s hidden problems

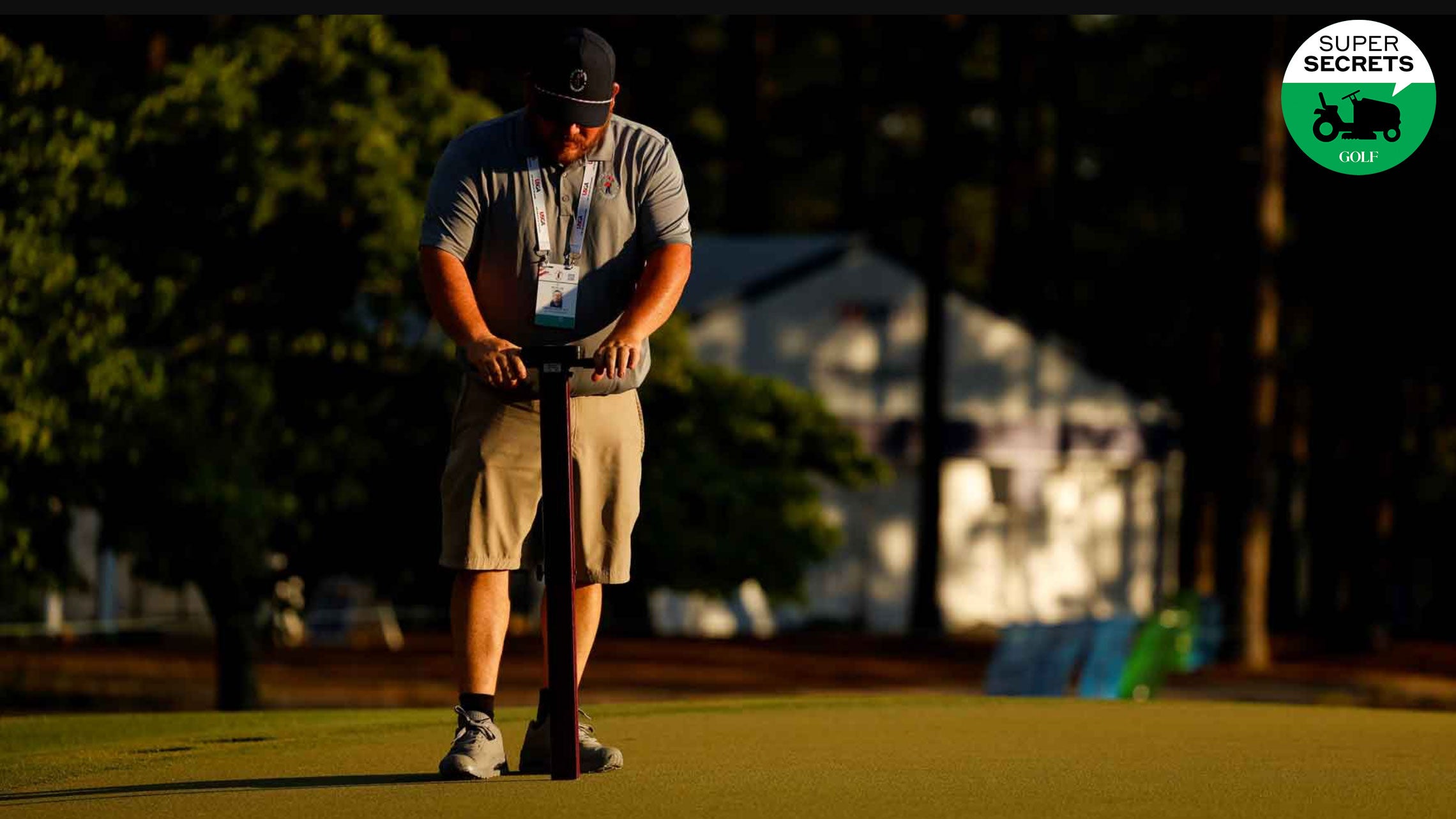

DJ McClellan is one of 24 volunteer apprentices who are helping care for Pinehurst No. 2 this week.

Kathryn Riley/USGA

Like the competitors at the 2024 U.S. Open, DJ McClellan is reading the greens carefully this week. He is tasked with monitoring soil-moisture levels on four putting surfaces at Pinehurst No. 2.

Championship setups require frequent tweaks, and McClellan, 36, knows all about adjustments. He’s made many in his life.

“You could say I’ve gone through a few things to get where I am today,” he says.

A North Carolina native, he started working in agriculture in his teens, farming cotton and other row crops, before following his father’s footsteps into law enforcement. For nearly seven years, he served as a sheriff’s deputy in a county jail, roughly an hour south of Pinehurst, a role he held until 2021.

“I’m an outdoor guy, and I didn’t like not being in sunlight,” McClellan says. Not working was not an option, though. Married, with a daughter, he had bills to pay. “I just knew that I was ready for something different.”

McClellan had always liked golf. He’d played it as a kid. But golf-course maintenance?

“I figured it was just cutting grass,” he says.

A fresh perspective came when McClellan caught wind of the USGA’s Greenskeeper Apprentice Program (GAP), an innovative initiative aimed at addressing a growing challenge in the industry. For golf-course operators, staffing has never been easy. In recent years, finding and retaining talent has only gotten tougher. In a 2022 member survey by the Golf Course Superintendents Association of America, respondents cited workforce issues as their greatest challenge, ahead of course conditioning and revenue-generation, with 70 describing the labor market as “bad” or “very bad.”

No wonder, really. Many course-maintenance jobs are hourly positions that pay less than jobs of a similar skill level, and allow little room for moving up. Why wake up before dawn and bust your butt in what you perceive as a dead-end gig if you can earn as much or more driving an Uber?

That’s the crux of the problem. Its roots run deep. But so do the solutions offered by GAP. Anchored in the Carolinas, the program provides tuition-free education for aspiring golf-course maintenance professionals, paired with paid-on-the-job training at partner courses. Apprentices take a range of turf-related classes — soil science, plant fertility, irrigation, and on — then apply those lessons directly in the field.

The goal is to produce a skilled workforce with opportunities for advancement, backed by financial support that allows those workers to stick around to learn and grow — whether they are young people starting out or older candidates making mid-life career changes.

“It’s important to give people a sense of ownership in their jobs” says GAP program coordinator Carson Letot. “When you teach them the science behind what they’re doing and give them a chance to apply those learnings in the real world, it creates that sense of ownership. Those people are going to feel more committed to their jobs, and they’re more likely to stay in them.”

After a successful pilot run for GAP last year (of the 19 members of the inaugural graduating class, 70 percent received promotions, and 18 were given more prominent leadership roles), the USGA and donors doubled down on the program in 2024, committing another $1 million to fund in-class and on-course education over the next five years at Sandhills Community College, in the Pinehurst area, along with a program in Horry-Georgetown Technical College, in Myrtle Beach, which will start in 2025.

McClellan enrolled in GAP this year. As one of 18 members of the 2024 class, he has combined his studies with the ultimate outdoor classroom: working at Pinehurst Resort, where he has risen to the role of foreman at Pinehurst No. 1.

This week, he has even more on his plate. Throughout the tournament, 24 members of the ’23 and ’24 GAP classes are assisting Pinehurst’s agronomy staff in the preparation and care of Pinehurst No. 2. Among them is Matt Fick, 25, a Georgia native who worked in residential and commercial lawn, before landing a job as a spray technician at Champions Retreat, a private club in Augusta that hosts the preliminary rounds of the Augusta National Women’s Amateur.

Fick wasn’t a big golfer. Soccer and football had always been his sports. But the first time he saw a push-mower cutting a green to tiny fractions of an inch, “my mind was blown,” he says.

It was at the ANWA that he learned about the GAP program. The rest is history.

“I’ve always been the kind of person who is going to try to make the most of any opportunity,” Fick says. “I just put my head down and strive to put myself in the best position I can.”

At the U.S. Open this week, he’s on front-nine bunker duty at Pinehurst No. 2, while his friend and classmate, McClelland, handles moisture readings on the 10th, 12th, 14th and 15th greens. Their shifts begin pre-dawn and end after dark. Neither man would want it any other way. Each has thoughts of someday becoming a superintendent. One step at a time.

In life, as in golf, you never know what tomorrow might bring.